28 May What We Do… Otolith Lab

Somewhere in Southern Southeast Alaska another sting operation has just concluded, and things are about to get very interesting…… “MR. SALMON, YOU’VE JUST BEEN CAUGHT. I NEED TO SEE YOUR I.D.”.

Southern Southeast Regional Aquaculture Association (SSRAA) releases millions of salmon into the wild every year. One very important part of that process is being able to keep track of those fish, especially when they return over the years and are caught by fishermen. SSRAA employs several methods for identifying the fish we release: coded wire tagging, thermal marking, and dry marking.

Coded wire tagging (CWT) is the “old school” method. Juvenile salmon, from about 1 gram to 20+ grams, are injected in the snout with a tiny piece of magnetized wire that has a number (code) etched into it. The process is expensive, very labor intensive, and for the most part, no more than 10% of the fish receive a tag.

Photo #1: Full length Coded Wire Tag sitting on a penny. Actual length is approximately 1 mm.

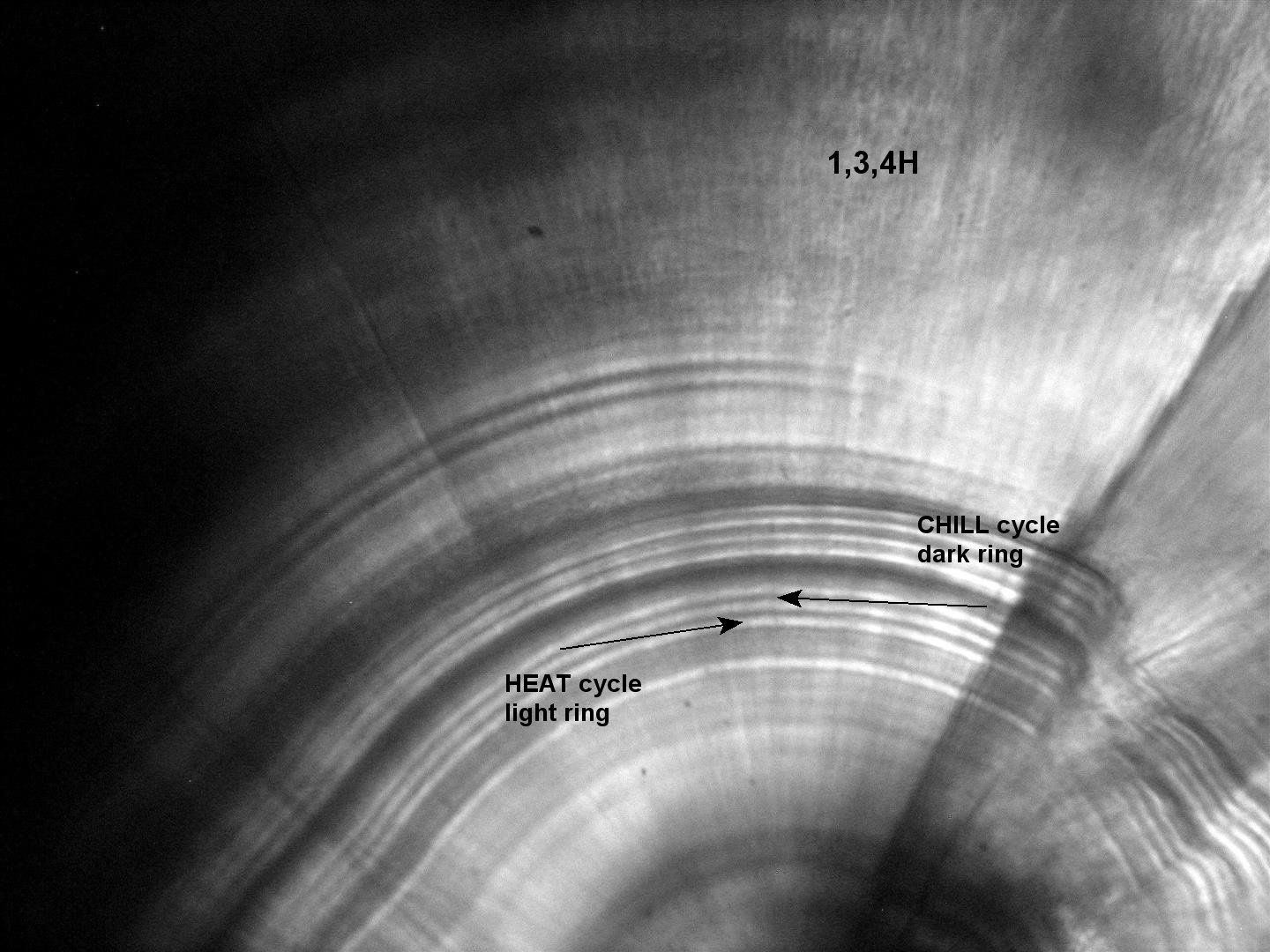

The next method, thermal marking, is used most often and on the greatest number of fish released by SSRAA. It’s a newer method; we used it for the first time in 1998 on sockeye. The mark is created on the otoliths, what most people call “ear bones”. (They are actually “ear stones” since they are composed mostly of calcium carbonate.) The process is very simple: the temperature of the incubation water is adjusted up or down approximately 4ºC.

Each adjustment produces a different “color” at the edge of the growing otolith. When the water becomes warmer, a lighter colored area is produced. When the water becomes cooler, a darker colored area is produced. Repeating this process produces a series of “rings”. These rings resemble tree rings, except that they are grouped together in bands that create a circular barcode. Each “group” of fish being released is given its own unique barcode identifying those fish and telling the early life history of each fish in great detail, including things like how it was raised and where it was released. We also are able to tell the exact age of the fish, how migration patterns and return timing may change, and so much more. Perhaps one of the greatest advantages of thermal marking is that not only are we able to mark all the fish at one time, but we can mark them before and/or after they have hatched.

PHOTO #2: A thermal marked chum otolith. Here the rings are formed by temperature changes in the incubation water. Each of these light and dark rings was created over a 12 hour period, with the exception of the last ring in each band. Since it’s expensive to heat water with a boiler, only the last 12 hours of the 2 day period between bands receives heated water. This results in a “smear”, where the last ring in a band becomes very wide. Three of them are visible here: one just below the arrowhead pointing to the heat cycle, and another just above the arrowhead pointing to the chill cycle. Can you find the third one?

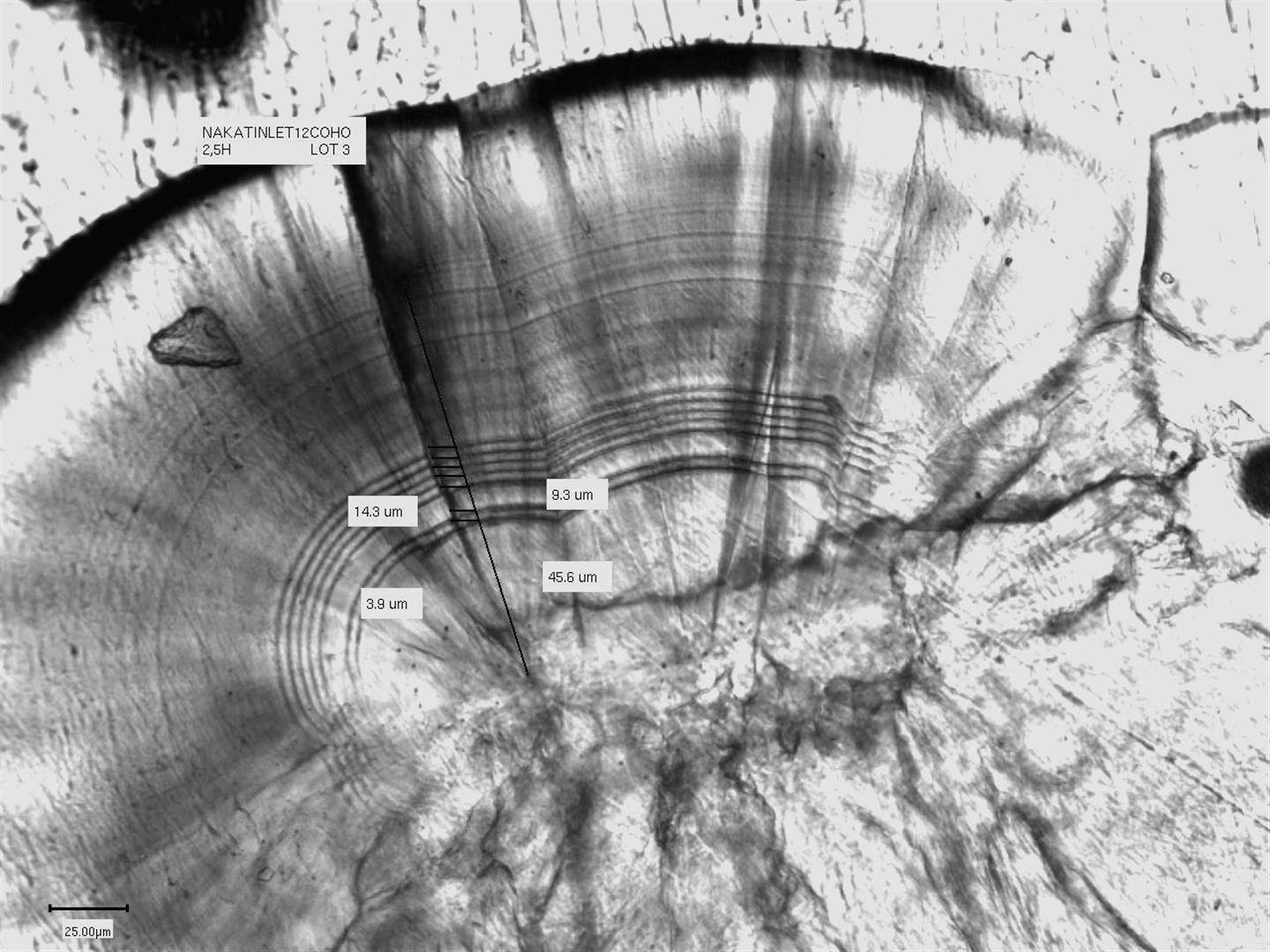

The last method is dry marking, also a newer method. SSRAA just started using this method in 2013 on a limited basis. While it can also mark every single fish, all at one time, it can only be used on fish (eggs) before they hatch. Incubator water is drained out for a period of time (usually 24 hours) and then reestablished (usually for 24 hours or several days). The result is very similar to a thermal mark.

PHOTO #3: A dry marked coho otolith. The first band of the mark has 2 rings, and the second band has 5 rings. Each dark ring was the result of moist eggs being exposed to the air for 24 hours. The light rings (the spaces between the dark rings) were caused by incubation water submerging the eggs for 24 hours. The light colored space between the 2 bands was created by submerging the eggs for a period of 4 days. When the final dark ring is made, the incubation water is turned back on and remains on thereafter. This mark is read as 2,5H. The “H” represents the hatch, and indicates that the entire mark was produced before hatching occurred, which is a requirement when dry marking.

There are 3 main reasons why SSRAA marks/tags all of the fish we release.

-

Some species and/or releases are required by Alaska Department of Fish & Game to have a certain percentage marked, using a particular method research.

-

Estimating the survival rate of a release; seeing the effects of different rearing strategies (release timing, release size, diet, etc.); detecting changes in return timing and routes; just about anything and everything that the fish do or that impacts them.

-

Documenting our contribution to the common property fisheries and all the other users of the resource.